I’ve been thinking about the humble cassette these past few days, almost pulling the trigger on Machinefabriek's cassette-only Sahara Mixtape album over the weekend, before halting the Paypal payment at the final screen. It's strange to see cassettes making a comeback, the underground/experimental music community in particular has re-embraced this old format in search of a warmer analogue sound (or perhaps anti-digital), but I remain unconvinced that they are nothing other than a cool retro novelty. I have an old Philips 3-in-1 unit to play tapes on, but I find it a cumbersome format - the sheer work involved in finding a favorite track, the endless fast-forwarding and rewinding, a nuisance compared with the needle-dropping precision of an LP or the laser-guided index of a CD. I had a pretty decent tape collection back in the early 90’s, mostly death metal cassettes that were picked up for swaps, or bought when an LP or CD edition wasn’t available, such as Soft White Underbelly, the sole studio album by Sweet Tooth, a fantastic, raucous power trio Justin Broadrick played in around the time of Streetcleaner. Earache issued the album in 1990 on vinyl and cassette (no CD) on their short-lived, one-release imprint Staindrop Records, and given Digby Pearson’s antipathy for re-issuing old Earache albums, I regret now that my tape is long gone.

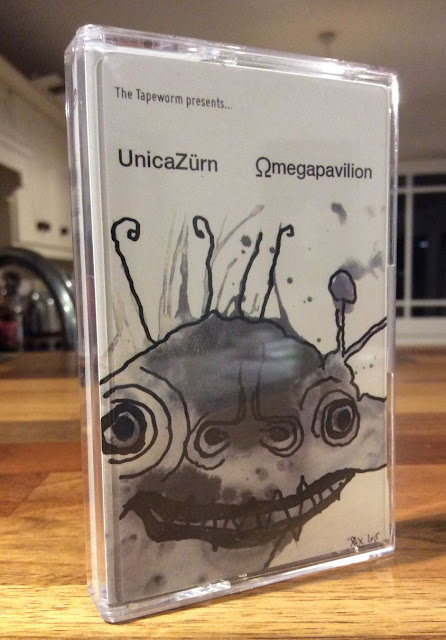

Good things come in small packages as the proverb goes and I can't ignore the fact that an awful lot of very good music is getting released on cassette only, and some of it looks rather lovely too, with designers taking a very imaginative approach to the limited space of the inlay card. Back in 2016, I actually did buy some music on cassette. Steve Thrower's dark ambient project UnicaZürn, released a cassette-only album entitled Omegapavilion, on the Tapeworm label and while I was a fan of UnicaZürn's 2009 album, the brilliant Temporal Bends, I think it was Danielle Dax's gorgeous artwork that finally pushed me into buying the album, the first cassette I had bought in over 25 years. When this little package first popped through my letterbox I spent days fondling the case like it was some strange fetishistic object, which of course it was - the tape now sits on the CD shelf and gets little play these days for fear that my Philips will mangle the tape ribbon. I just wish the two fantastic sides of Zeit-style cosmic weirdness were instead on a shiny compact disc, or made available as a download. I might still buy the Machinefabriek tape, but I know the digital file offered would most likely end up as the primary listening format and the cassette displayed as a sort of trophy add-on.

Monday, 25 February 2019

Wednesday, 20 February 2019

All that evidence of violence...

Years ago, before I was married, I often went to visit my mother in the country. She was still alive in those days. Her house, a little cottage, was surrounded by a garden a little garden, dreadfully neglected and overgrown. No one had tended it for many years and I don't think anyone had ever been in it. Even then, my mother was very ill. She almost never left the house. Still, amidst the ruin of the garden there was something that was, in its way, beautiful. Yes, now I know what it was. When the weather was fine, she often sat at the window looking out at the garden. She even had a special chair by the window. Once, though, I decided that I would tidy things up... in the garden, that is. I wanted to mow the grass, burn the weeds, prune the trees. On the whole, I wanted to redo the garden in my own taste with my own hands. Yes, simply to please my mother. And for two solid weeks I went at it with shears and a scythe. I dug and cut and sawed and weeded. I kept my nose to the ground, literally. And I took great pains to get it ready as soon as possible. My mother's condition grew worse, and she kept to her bed. But I wanted her to be able to sit by the window and see her new garden. In short, when I was finished and everything was ready, I took a bath put on fresh underwear, a new jacket, even a tie. Then I sat down in the chair to see what I'd made, through her eyes, as it were. I... I sat there... and looked out through the window. I had prepared myself to enjoy the sight. Anyway, I looked out the window and saw... What did I see? Where had all the beauty gone? The naturalness of it? It was so disgusting. All that evidence of violence...

Erland Josephson, The Sacrifice

Wednesday, 13 February 2019

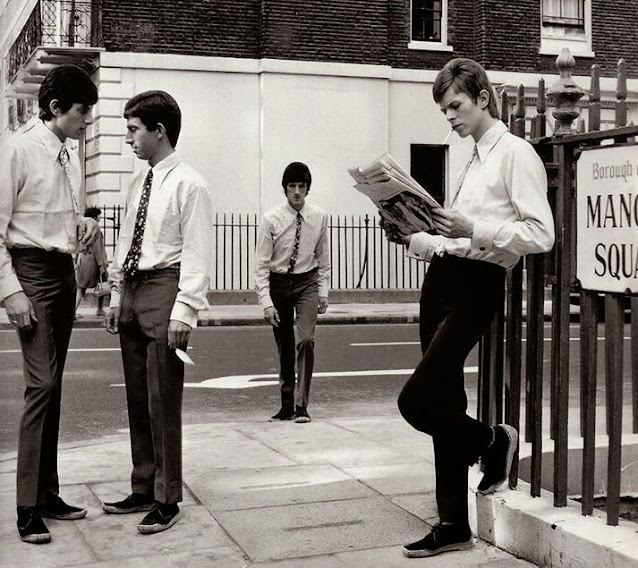

David Bowie: Finding Fame

I just want to say that you've given me more pleasure than I've had in a good few months of working, and I don't do gigs any more because I got so pissed off with working and dying a death every time I worked and it's really nice to have somebody appreciate me for a change

David Bowie, Glastonbury, 1971

Francis Whately’s latest Bowie documentary really ought to have been called The First Five Years, following the template of the director’s previous epoch-defining films, Five Years (2013) and The Last Five Years (2017). This third installment begins in 1966 and charts the years Bowie spent drifting thru a series of throwback rock n' roll groups and mod combos in search of an audience, before settling on a peculiar style of English music hall that seemed to please no one - songs like Rubber Band, Uncle Arthur and Please Mr. Gravedigger were a tad too quaint and whimsical for the average rock fan, but too weird and avant-garde for the Anthony Newley crowd. As with the previous films, Whately wisely lets the interviewees do the talking and there are some terrific anecdotes along the way from friends and collaborators such as regulars Tony Visconti, Carlos Alomar, George Underwood, Woody Woodmansey, and Rick Wakeman, plus valuable contributions from members of The Lower Third, and The Riot Squad. Bowie himself is represented by some judicious audio extracts and his comments are often touching and surprisingly honest about his formative years.

Casual viewers who assumed Bowie came fully formed with Space Oddity, might balk at the oddities heard throughout the documentary, and perhaps to spare the blushes of seasoned fans, the song selection reflects his best work at the time - The London Boys, There Is A Happy Land, When I Live My Dream, Come and Buy My Toys, Let Me Sleep Beside You. No overview of this era could get away without mention of The Laughing Gnome and it's left to Carlos Alomar to rehabilitate this irrepressible little pest of a song, cheerfully exploring the similarities between The Laughing Gnome and The Velvet Underground's I'm Waiting for the Man. And while he's not terribly convincing, it is great fun to hear the Station to Station guitarist scatting along to what is most likely the quintessential bête noire of Bowie songs.

Some of the most interesting and compelling testimony comes from two women who were particularly close to Bowie at both ends of the 60's. Kristina Amadeus (Bowie's cousin, no less) recalls family life at the Jones home at 4 Plaistow Grove and the contrary relationship Bowie had with his parents, his mother in particular, who's frequently described by those who knew her at the time as being cold and withdrawn. Interestingly Kristina plays down the mythology that has grown up around Terry Burns, Bowie's troubled half-brother who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, a condition that served Bowie well when he re-cast Terry as a sort dark spectral presence in his life, and claimed that insanity was a hereditary family curse. Another coup for the documentary is the rare participation of Bowie's first great love Hermione Farthingale, who speaks about their year long romance with great tenderness, and reads out a letter Bowie sent her whilst touring with Lindsay Kemp's mime production Pierrot In Turquoise ("Remember that I love you, and be gooder than good, forever, David"). The couple went their separate ways when Hermione joined the cast of the MGM musical Song of Norway, sensing that Bowie's career was following a different trajectory to her own. Bowie was left broken hearted ("I didn't get over that for such a long time, it really broke me up"), but it led to Bowie writing one of his finest and most autobiographical songs, Letter to Hermione, and considering the crucial involvement of Angel Barnett in the next phase of Bowie's life, perhaps it was just as well. Some of the material showcased throughout the documentary was astonishing.

The Bowie Estate was unusually generous in supplying long lost recordings, demos and rough sketches - some of which I had only previously encountered on lo-fi boots, and the understandable absence of performance footage is made up for with a wealth of rare photographs. In one amusing aside, echoing Decca's famous rejection of The Beatles, Lower Third drummer Phil Lancaster reads the withering summation of the group's ill fated 1965 audition for the BBC penned by a clearly unimpressed talent scout. It's an incredible document. "There is no entertainment in anything they do. It's just a group and very ordinary, too, backing a singer devoid of personality". Thankfully Bowie held his nerve.

The documentary's feature length was generous but still there were a few omissions, notably the involvement of manager Ken Pitt and his attempts to revive Bowie's foundering career, which included landing Bowie some film work. Whately could hardly be criticized for skipping over Bowie's inconsequential 3-second walk on (or rather slide off) appearance in the 1969 film The Virgin Soldiers, but I thought it rather disappointing that no mention was made of Bowie's haunting turn in Michael Armstrong's interesting 1967 short The Image. Bowie later dismissed the film as "awful" but it remains Bowie's most dramatic film appearance up to The Man Who Fell To Earth.

The documentary also seemed to lurch clumsily in the final section between the recording of The Man Who Sold the World and the success of the Ziggy Stardust-era, with Hunky Dory disposed of with a quick flash of the album cover as if Whately wasn't quite sure what to do with it. And for all the scorn heaped on The Laughing Gnome, it's a pity no one made the connection between Bowie's use of the high-pitched voice for that song and the cartoon voices heard on Hunky Dory's closing song The Bewlay Brothers, arguably, Bowie's greatest song. Also, there was no mention of Peter Noone’s cover version of Oh! You Pretty Things, which didn't make its author a household name but must have offered some consolation when it climbed to a respectful 12th position in the UK charts in May 1971. I'm nip-picking of course. These minor objections do not alter the fact that Finding Fame is one of the more comprehensive Bowie documentaries to emerge since his passing and needless to say it is absolutely essential viewing. If you missed the initial BBC2 screening, the film is currently available to view on the BBC iplayer.

Friday, 8 February 2019

Maurizio Bianchi’s Mectpyo Box

I'm currently trawling thru Maurizio Bianchi’s Mectpyo Box, an excellent 10-disc collection gathering up the maestro’s early 80’s albums and rare compilation appearances. One gets a sense that Bianchi and contemporaries Pierpaolo Zoppo and Kevin Tomkins were frustrated with Throbbing Gristle's desire to move away from the harsh electronics and shock tactics of their early studio recordings, and there’s a certain naive storming-the-citadel feeling to this early wave of Industrial Music, as if the young turks were showing the older veterans how the music was meant to sound.

The Mectpyo Box spans some four years of feverish activity before Bianchi ceased making music to became a Jehovah’s Witness, as unlikely as that seems. Or perhaps not, given album titles like Das Testament, The Plain Truth, and Armaghedon. In fact, it might have been Bianchi's interest in spiritual matters that stood his music apart from misanthropic power electronic outfits like Mauthausen Orchestra and Sutcliffe Jügend. In the wake of the 1981 albums Symphony for a Genocide and Menses, which both featured churning noise and lashings of free form psychedelic electronics, Bianchi's music began to reflect a more melancholic mood characterized by his use of space and atmosphere. The two side-long pieces on Mectpyo Bakterium sound like they might have strayed from an experimental science fiction film, the second track in particular, puts in mind Gino Marinuzzi Jr.'s score for Planet of the Vampires. The 1982 album Neuro Habitat introduced a more ambitious effects-laden sound and that same year Bianchi produced one of his key works, Regal, which was distinguished by a more restrained, even soothing Kosmiche flavor. Das Testament another work from 1982, is by contrast, a stark and minimalist affair which reduced the sound to loops of low end apocalyptic rumblings and percussive effects. The 1983 album The Plain Truth returns to the disturbing, spectral ambiance of Regal, while 1984's Armaghedon, consists of two lengthy and unnerving soundscapes originally composed for a film, and perhaps it's appropriate that the first track is reminiscent of Wayne Bell and Tobe Hooper's musique concrète score for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Packaging wise, the hefty outer box is austerely designed, sporting Bianchi's logo on the front cover, with each of the albums housed in attractive card sleeve replicas of their original issues complete with liner notes and reviews from the underground press. Rounding out the box are 35 inserts containing artwork, photo collages and various writings by Bianchi on the experimental music of the era, including one impenetrable essay on TG !

The Mectpyo Box spans some four years of feverish activity before Bianchi ceased making music to became a Jehovah’s Witness, as unlikely as that seems. Or perhaps not, given album titles like Das Testament, The Plain Truth, and Armaghedon. In fact, it might have been Bianchi's interest in spiritual matters that stood his music apart from misanthropic power electronic outfits like Mauthausen Orchestra and Sutcliffe Jügend. In the wake of the 1981 albums Symphony for a Genocide and Menses, which both featured churning noise and lashings of free form psychedelic electronics, Bianchi's music began to reflect a more melancholic mood characterized by his use of space and atmosphere. The two side-long pieces on Mectpyo Bakterium sound like they might have strayed from an experimental science fiction film, the second track in particular, puts in mind Gino Marinuzzi Jr.'s score for Planet of the Vampires. The 1982 album Neuro Habitat introduced a more ambitious effects-laden sound and that same year Bianchi produced one of his key works, Regal, which was distinguished by a more restrained, even soothing Kosmiche flavor. Das Testament another work from 1982, is by contrast, a stark and minimalist affair which reduced the sound to loops of low end apocalyptic rumblings and percussive effects. The 1983 album The Plain Truth returns to the disturbing, spectral ambiance of Regal, while 1984's Armaghedon, consists of two lengthy and unnerving soundscapes originally composed for a film, and perhaps it's appropriate that the first track is reminiscent of Wayne Bell and Tobe Hooper's musique concrète score for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Packaging wise, the hefty outer box is austerely designed, sporting Bianchi's logo on the front cover, with each of the albums housed in attractive card sleeve replicas of their original issues complete with liner notes and reviews from the underground press. Rounding out the box are 35 inserts containing artwork, photo collages and various writings by Bianchi on the experimental music of the era, including one impenetrable essay on TG !

Wednesday, 6 February 2019

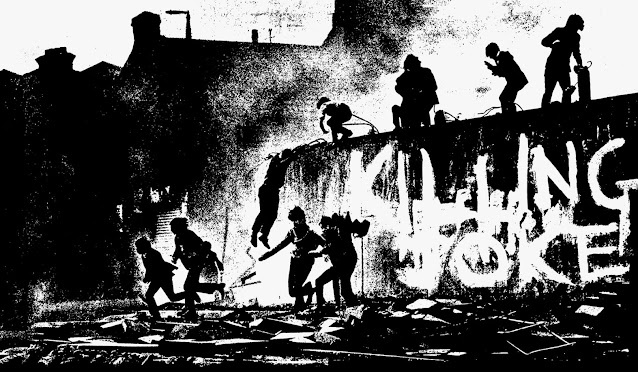

Don McCullin and a Wall in Derry

A supplement to my previous post about photographing the Troubles... Yesterday I caught the hour long BBC4 documentary Don McCullin: Looking for England, in which the great photojournalist, now in his 80’s, takes a journey around the country in search of contemporary English life in all its richness and diversity. It’s a rather lovely and gentle film, full of compassion and kindness, but its timing did jog a memory of a series of photographs McCullin took during a tour of Northern Ireland in 1971 just as the Troubles were intensifying. The images were collected for a 12-page Sunday Times photographic supplement entitled War on the Home Front (19 December 1971), and I was specifically thinking of McCullin’s striking photograph depicting a gang of Derry youths scrambling over a wall to escape a cloud of tear gas fired by British soldiers. It may not be one of the more emblematic photographs that emerged from the conflict but it’s surely one of the most widely seen – in 1980 Killing Joke adapted the image for the cover of their debut album, which served as my first introduction to the work of Don McCullin.

I was curious to hear more about the image and McCullin’s experiences in Derry so I turned to his excellent 1992 autobiography Unreasonable Behaviour...

Further reading: Whilst preparing this entry, I stumbled across this post by New York blogger Alex who writes about the Killing joke album cover: Back Again to the Bogside: Revenge of the Killing Joke Wall

I was curious to hear more about the image and McCullin’s experiences in Derry so I turned to his excellent 1992 autobiography Unreasonable Behaviour...

I can vouch for the effectiveness of the CS gas used by the British army against riotous demonstrators in Northern Ireland. The first time I received a serious dose, in the Bogside area of Derry later in 1971, I went blind. The demonstration had become ugly, with rubber bullets and great shards of glass from shattered milk bottles flying around. Then, suddenly, a tremendous burning sensation seized my nose and throat, and forced me to close my eyes. I can remember groping my way back from the fray and leaning my face to a wall. I was thinking that if I could zone in on an area of total darkness and flick my eyes open, the trouble would go away. It didn’t work. As I stood there in total darkness—eyes, nose, throat, ears, mouth, all burning - I felt a great lump in my back. It was a rubber bullet. Behind me a voice said, ‘The bastards. The inhuman bastards.’

I had to pass the British soldiers posted at the street corner. I held up my cameras prominently as the badge of my profession, and saw the looks of scorn and heard the swearing under their breath. As far as they were concerned I was consorting with the enemy which they had just tear-gassed.

Further reading: Whilst preparing this entry, I stumbled across this post by New York blogger Alex who writes about the Killing joke album cover: Back Again to the Bogside: Revenge of the Killing Joke Wall

Monday, 4 February 2019

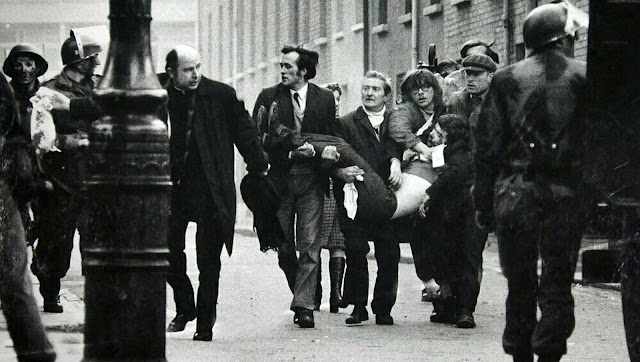

Shooting the Darkness

We took pictures, not sides... Paul Faith, photojournalist

Shooting the Darkness, a superb new 52min television documentary that screened last week in Ireland examines the work of the photojournalists who captured the brutality of the Troubles through the lens of their cameras. Unlike celebrated combat photographers like Robert Cappa and Eddie Adams who followed conflict around the world, the men profiled in this documentary found war raging on their doorsteps. Before the Troubles several of the photographers were engaged with routine assignments - snapping dignitaries visiting Belfast or in the case of Stanley Matchett, photographing The Dubliners for the album cover of their 1967 album More Of The Hard Stuff. But after the events of Bloody Sunday, their work took on a greater significance as the bore witness to the beatings, bombings, assassinations and wholesale murder that emerged from the conflict. Many of their images flashed around the world, indeed, the devastated streets of Belfast were re-created by Italian documentary film makers Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi for their 1975 fantasy film Mondo Candido, a very early example of the Troubles dramatized on film.

One thing that emerges from Shooting the Darkness is the courage of the photographers, who often put themselves in harm’s way to get a shot of the event they were covering, from large-scale angry disturbances to clandestine invitations by paramilitaries to photograph their dead (which were often fraught with nerves by both parties). The documentary is brimming over with harrowing images of the Troubles, and many of the photographs did not become headline news, but as photographer Hugh Russell opines, even the shots of anonymous, insignificant victims executed in lonely places can pack as much tragedy into their single frames as some of the more high-profile events. From the documentary I’ve selected a few of the more striking images and the stories behind them...

▲ Stanley Matchett's iconic photograph of the body of Jack Druddy being carried down Churchill Road, Derry City after he was shot dead on Bloody Sunday, 30 January 1972, when members of the British Parachute Regiment opened fire on Civil Rights marchers using live ammunition. The image of Catholic priest Edward Daly leading the group to safety whilst waving a bloody handkerchief has become one of the most enduring images of the Troubles. Reflecting on the image, Matchett found a striking parallel between Druddy's body and the depiction of Christ in Caravaggio's painting, The Entombment of Christ. Such was the power of the image, it was later recreated for a mural in 1997 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the atrocity.

*****

▲ Alan Lewis' photograph of an ambulance driver carrying the body of a baby found in the devastation of the Balmoral Furniture Company on the Shankill Road, blown up by the IRA in December 1971. This was in fact the second baby removed from the wreckage that day, Alan Lewis was unable to capture the shot of the first body taken from the blast due to his horror of the event, but 20mins later when the second baby emerged, he composed himself sufficiently to record the moment. Prominent Unionist politician David Ervine later told Alan Lewis that his photograph had been a powerful recruitment tool for loyalists paramilitaries, much to the photographer's distress, who had hoped the image would steer people away from the path of violence.

*****

▲ Trevor Dickson's photograph of a young man tarred and feathered in the Fall's Road area of Belfast in 1971. This was a humiliating and degrading punishment routinely handed out by the IRA throughout the 70's to people accused of minor crimes and transgressions. This is an example of a photograph stage managed by the IRA. Trevor Dickson was tipped off by an intermediary that the punishment was due to take place and was invited to the scene to capture the result with his camera. The photographer recalled that as he was taking his shots, an outraged priest came upon the scene and tried to stop him, but was moved on by the IRA so Dickson could work unhindered.

*****

▲ Alan Lewis' photograph of the killing of John Downes in Andersonstown, at a nationalist rally in west Belfast in August 1984. Like, Eddie Adams' iconic Saigon Execution photograph, Lewis' captures that frozen moment in time when RUC officer Nigel Hegerty fired a plastic bullet at point blank range at Downes - crucially the puff of smoke from the discharged weapon is clearly visible as Downes recoils from the fatal impact. Eye-witness accounts on the day claim that an unprovoked RUC fired plastic bullets on the assembled crowd, as IRA fundraiser Martin Galvin, who was banned from entering the North, was due to make an address outside Sinn Fein offices. In the melee that followed, Downes ran into to the path of the RUC man who fired a round into his chest, the proximity of the gun would proved fatal.

*****

▲ Paul Faith's photograph of the late Sinn Féin vice President Martin McGuinness pictured with masked IRA men at the funeral of Brendan Burns in February 1988, another example of the publicity-savvy Republican moment. At this point in the Troubles, the British Government had decreed that Republican funerals be strictly family affairs, and placed a ban on any armed shows of force, a hallmark of IRA funerals. On this occasion, a heavy military presence was tracking the funeral cortège, and when masked and camouflaged honor guards appeared carrying the coffin, draped with an Irish flag, riot police swooped in to make arrests.Their efforts were impeded by the crowd who pushed against them and in the confusion, the IRA men were spirited away, but not before Paul Faith was able to capture a moment of defiance, a considerable publicity coup for the Republican movement.

*****

▲ One of Martin Nangle's shots of plain-clothed British army corporals Derek Wood (pictured above, clutching a handgun) and David Howes moments before they were pulled from their car by an angry mob after mistakenly driving down the path of a Republican funeral in March 1988. One of the more distressing images seen in the documentary, the men who were initially believed to be loyalists were savagely beaten, stabbed, stripped and later executed. This photograph is an example of how a tense situation like a politically-charged funeral could quickly descend into barbarity. When the mob descended upon the car, photographers and news cameramen were ordered by Sinn Fein stewards to give up their incriminating footage, but instead Nangle surreptitiously swapped his footage with a roll of unused film, which in turn was surrendered. It's the kind of quick-thinking coup any photojournalist would admire, but Nangle admits in the documentary that he can take no pleasure in the safe-guarding of these terrible images.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)