We took pictures, not sides... Paul Faith, photojournalist

Shooting the Darkness, a superb new 52min television documentary that screened last week in Ireland examines the work of the photojournalists who captured the brutality of the Troubles through the lens of their cameras. Unlike celebrated combat photographers like Robert Cappa and Eddie Adams who followed conflict around the world, the men profiled in this documentary found war raging on their doorsteps. Before the Troubles several of the photographers were engaged with routine assignments - snapping dignitaries visiting Belfast or in the case of Stanley Matchett, photographing The Dubliners for the album cover of their 1967 album More Of The Hard Stuff. But after the events of Bloody Sunday, their work took on a greater significance as the bore witness to the beatings, bombings, assassinations and wholesale murder that emerged from the conflict. Many of their images flashed around the world, indeed, the devastated streets of Belfast were re-created by Italian documentary film makers Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi for their 1975 fantasy film Mondo Candido, a very early example of the Troubles dramatized on film.

One thing that emerges from Shooting the Darkness is the courage of the photographers, who often put themselves in harm’s way to get a shot of the event they were covering, from large-scale angry disturbances to clandestine invitations by paramilitaries to photograph their dead (which were often fraught with nerves by both parties). The documentary is brimming over with harrowing images of the Troubles, and many of the photographs did not become headline news, but as photographer Hugh Russell opines, even the shots of anonymous, insignificant victims executed in lonely places can pack as much tragedy into their single frames as some of the more high-profile events. From the documentary I’ve selected a few of the more striking images and the stories behind them...

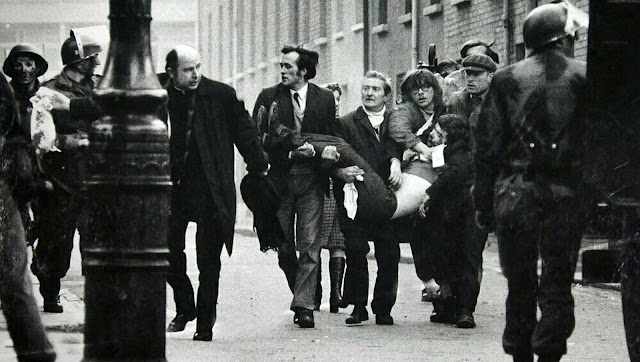

▲ Stanley Matchett's iconic photograph of the body of Jack Druddy being carried down Churchill Road, Derry City after he was shot dead on Bloody Sunday, 30 January 1972, when members of the British Parachute Regiment opened fire on Civil Rights marchers using live ammunition. The image of Catholic priest Edward Daly leading the group to safety whilst waving a bloody handkerchief has become one of the most enduring images of the Troubles. Reflecting on the image, Matchett found a striking parallel between Druddy's body and the depiction of Christ in Caravaggio's painting, The Entombment of Christ. Such was the power of the image, it was later recreated for a mural in 1997 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the atrocity.

*****

▲ Alan Lewis' photograph of an ambulance driver carrying the body of a baby found in the devastation of the Balmoral Furniture Company on the Shankill Road, blown up by the IRA in December 1971. This was in fact the second baby removed from the wreckage that day, Alan Lewis was unable to capture the shot of the first body taken from the blast due to his horror of the event, but 20mins later when the second baby emerged, he composed himself sufficiently to record the moment. Prominent Unionist politician David Ervine later told Alan Lewis that his photograph had been a powerful recruitment tool for loyalists paramilitaries, much to the photographer's distress, who had hoped the image would steer people away from the path of violence.

*****

▲ Trevor Dickson's photograph of a young man tarred and feathered in the Fall's Road area of Belfast in 1971. This was a humiliating and degrading punishment routinely handed out by the IRA throughout the 70's to people accused of minor crimes and transgressions. This is an example of a photograph stage managed by the IRA. Trevor Dickson was tipped off by an intermediary that the punishment was due to take place and was invited to the scene to capture the result with his camera. The photographer recalled that as he was taking his shots, an outraged priest came upon the scene and tried to stop him, but was moved on by the IRA so Dickson could work unhindered.

*****

▲ Alan Lewis' photograph of the killing of John Downes in Andersonstown, at a nationalist rally in west Belfast in August 1984. Like, Eddie Adams' iconic Saigon Execution photograph, Lewis' captures that frozen moment in time when RUC officer Nigel Hegerty fired a plastic bullet at point blank range at Downes - crucially the puff of smoke from the discharged weapon is clearly visible as Downes recoils from the fatal impact. Eye-witness accounts on the day claim that an unprovoked RUC fired plastic bullets on the assembled crowd, as IRA fundraiser Martin Galvin, who was banned from entering the North, was due to make an address outside Sinn Fein offices. In the melee that followed, Downes ran into to the path of the RUC man who fired a round into his chest, the proximity of the gun would proved fatal.

*****

▲ Paul Faith's photograph of the late Sinn Féin vice President Martin McGuinness pictured with masked IRA men at the funeral of Brendan Burns in February 1988, another example of the publicity-savvy Republican moment. At this point in the Troubles, the British Government had decreed that Republican funerals be strictly family affairs, and placed a ban on any armed shows of force, a hallmark of IRA funerals. On this occasion, a heavy military presence was tracking the funeral cortège, and when masked and camouflaged honor guards appeared carrying the coffin, draped with an Irish flag, riot police swooped in to make arrests.Their efforts were impeded by the crowd who pushed against them and in the confusion, the IRA men were spirited away, but not before Paul Faith was able to capture a moment of defiance, a considerable publicity coup for the Republican movement.

*****

▲ One of Martin Nangle's shots of plain-clothed British army corporals Derek Wood (pictured above, clutching a handgun) and David Howes moments before they were pulled from their car by an angry mob after mistakenly driving down the path of a Republican funeral in March 1988. One of the more distressing images seen in the documentary, the men who were initially believed to be loyalists were savagely beaten, stabbed, stripped and later executed. This photograph is an example of how a tense situation like a politically-charged funeral could quickly descend into barbarity. When the mob descended upon the car, photographers and news cameramen were ordered by Sinn Fein stewards to give up their incriminating footage, but instead Nangle surreptitiously swapped his footage with a roll of unused film, which in turn was surrendered. It's the kind of quick-thinking coup any photojournalist would admire, but Nangle admits in the documentary that he can take no pleasure in the safe-guarding of these terrible images.

No comments:

Post a Comment