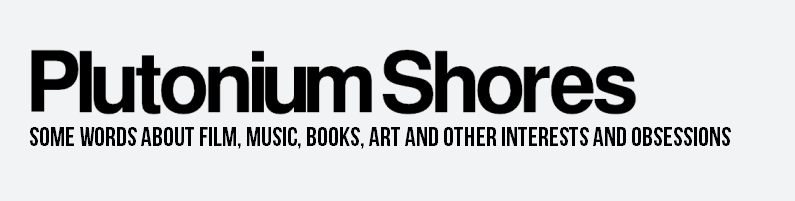

All this talk has me feeling nostalgic for my old Artificial Eye set and for this post, I dug it out from among the few VHS tapes I still own. I've always been fond of the Artificial Eye aesthetic - the uniformity of design, the clean organization of titles and text, the judicious use of stills and the instantly recognizable gray sleeve which gave an air of austerity and gravitas that I felt was entirely appropriate for titles like L'Atalante, Andrei Rublev, Les Enfants Du Paradis, i.e. serious world cinema. Looking at the Christ Stopped at Eboli sleeve now and seeing Derek Malcolm's name, I'm reminded of how much star wattage critics like Malcolm (The Guardian), Philip French (The Observer), and Geoff Andrew (Time Out) had back in the 90's...

Wednesday 17 June 2020

Christ Stopped at Eboli....on VHS

Very pleased to hear Criterion are adding Francesco Rosi's 1979 masterpiece to the Collection in September. I'm hoping for a simultaneous UK release but either way, I'll be adding this to my own collection even if it means getting the more expensive US import - some things are worth the extra cash. It's been at least twenty years since I last saw Christ Stopped at Eboli and I retain very warm, impressionistic memories of the film - the dusty, impossibly remote town where the film is set, the strange and fascinating customs and superstitions of the townsfolk, and a career-best performance from Gian Maria Volonte. If Christ did stop at Eboli, I stopped at VHS - the 1992 Artificial Eye VHS edition that is, which contained the long 3½ hr version of the film spread over two tapes. In 2006, UK label Infinity Arthouse put out the film on DVD but it was a huge disappointment, containing a 145min abridged version of the film, but worse still, the DVD transfer was extremely poor, the image riddled with ghosting instances and darker interior scenes that were rendered near unwatchable. So the forthcoming Criterion Blu-Ray is a genuine cause for excitement. With the release some months away, this gives me time enough to finally read the Carlo Levi memoir the film is based on, and perhaps revisit Arrow's Taviani Brothers collection.

Tuesday 16 June 2020

The Kill Bill Diary

It could have been so different, as David Carradine reminds us in the second entry of his 2004 memoir The Kill Bill Diary. It's March 2002 and for the past year Warren Beatty has been courted by Quentin Tarantino to the play the part of Bill. The 65 year old Beatty however has grown increasingly weary of the amount of time and effort the part requires, and when Tarantino suggests Beatty play Bill "like David Carradine", a fed up Beatty shoots back with "Why don't you offer it to David ?" Two weeks later Carradine along with his fellow Deadly Viper Squad of actors are in the thick of a grueling month-long, pre-shoot training regime learning martial arts and wire work under the tutelage of Yuen Wu Ping. And Carradine is enjoying every moment of it.

Written in a breezy, unpretentious style, The Kill Bill Diary is an interesting, sometimes fascinating account of David Carradine’s unlikely late career bump up to the A-list movie-making league after two decades worth of straight to video crap. Carradine’s reputation rests mostly on his 70's work, having made films for Martin Scorsese, Roger Corman, Robert Altman, Hal Ashby, Walter Hill and lest we forget Ingmar Bergman, plus he created a television icon as Caine, the wandering Shaolin monk in Kung Fu. But as the 80’s wore on Carradine’s increasingly erratic lifestyle reduced him to the status of jobbing actor taking fast pay checks for exploitation quickies. Carradine’s book doesn't rake over the ashes of the years spent languishing in the margins; he’s more content to spin a yarn about making Bound for Glory or The Long Riders, but what emerges most strongly from the diaries is Carradine's joy at finally landing the big fish (and director) he has been waiting for his entire career.

Those looking for a detailed look at the making of Kill Bill will be disappointed. Carradine has little interest in recording the nuts and bolts of film-making and perhaps to bolster that aspect of the book, he lazily borrows two set reports written by Harry Knowles. The focus instead is on Carradine's interactions with his fellow actors (he's especially generous in his praise for Uma Thurman and Michael Madsen) and his collaboration with Quentin Tarantino, here displaying a Wellesian level of energy and enthusiasm on set, inventing dialogue and scenes moments before they are shot. One peripheral but noteworthy character in the book is Rob Moses, whom Carradine describes as his "personal trainer and guitar buddy". Their twenty-year friendship was one of the more important relationships in Carradine's life and the actor had come to rely on him, so much so that he endeavored to get Moses attached to the production and served as Carradine's driver to and from locations. I had to wonder if Tarantino took some inspiration from this when writing Once Upon A Time In Hollywood.

Carradine steers clear of gossip and controversy for the most part, but there are a few grumbles of complaint along the way. Carradine is candid about his perilous finances (a string of ex wives and a taste for the good life will do that) and moans that his fee for the film was strictly scale (as was the rest of the cast) and the lengthy shoot resulted in him turning down several film offers and lucrative work on the convention circuit signing autographs (I presume the diary was Carradine's idea to squeeze a little extra revenue out of the film). Carradine records his irritation with Miramax for reprimanding the actor for various faux pas made during the film's promotional campaign - most seriously, when Carradine prematurely announced to a journalist that the original film would be split in two. Incidentally, Harvey Weinstein makes a few cameo appearances in the book, and is an intimating presence. Carradine refers to him at him at one point as a "master of the universe", (a seemingly complimentary but perhaps a knowingly ambiguous description), and admits "Harvey's not someone you want to be mad at you". Elsewhere Carradine writes: "Harvey showed up with a young actress in whom he is showing an interest" which prompts a shudder.

As I came to the end of The Kill Bill Diary, I felt a touch of sadness that Carradine never benefited from his change of fortune. As Carradine closes out his work on the film, with a whirlwind of globe-trotting promotion, Carradine is optimistic that better roles in bigger films were to come following his acclaimed performance in Kill Bill Vol. 2. But despite the prestige of appearing as the titular character in a Quentin Tarantino film, Carradine never did escape the low-budget film circuit where he continued to work until he was found dead in a Bangkok hotel room in 2009 in what is best described as strange circumstances.

In preparation for reading the book, I watched Kill Bill Vol 1 and 2 back to back, and it was interesting to revisit them in one single sitting. In fact this was my first time seeing the films together, strange considering I've owned the Japanese DVDs since 2004. Probably I was holding off for a release of the long rumored Whole Bloody Affair edition which has had a few select theatrical screenings but has yet to emerge on home video. But now that I’ve seen both films together, I have to wonder though how they ever knitted together in the first place, considering how distinctive both films are from each other - Vol 1, the fast, flashy, psychedelic blood feast, and Vol 2. the languid, introspective character study.

I suspect Quentin Tarantino had originally envisioned Kill Bill as a big take-the-day-off-work roadshow event a 4-hour magnum opus deserves, but eventually conceded that the epic length was too demanding for theatrical audiences. And to retain as much of his director's cut as possible, he was forced to split the film into two easily digestible halves. I now think that this was the best thing for the film, not because it breaks up the excessive run time, but because the story (assuming it follows the structure of Vol.1 and 2), no longer peaks much too early with the House of Blue Leaves massacre. I wonder had the original 4-hour version come out in 2003 would audiences have criticized the film for the quite drastic shift in tone from the stylish pyrotechnics of the first half to the comparatively quiet and reflective second half ? We'll never know. Almost 20-years later, it's impossible to think of Quentin Tarantino's fourth film as anything but his fourth and fifth and even if the Whole Bloody Affair does eventually get a home video or streamed release, it will surely be seen as a novelty item much like The Godfather Saga...

Monday 8 June 2020

A Fistful of Yojimbo

The current Covid-lockdown has given me opportunity to program films I would not ordinarily have time to see, and recently I enjoyed a double-bill of Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars. The plan was originally to follow up Yojimbo with the sequel Sanjuro, but the chance to revisit Leone's film in close succession was too good to pass up.1 Not having seen both films in many years, I had assumed Leone’s film lifted just the bare outline of the story (á la The Magnificent Seven and Seven Samurai) but the borrowing was more substantial than I had remembered, with plot points, characters, even shots from Yojimbo reappearing in Leone's film with only a few minor tweaks. In fact much of the delight of watching both films together is how frequently they interlock, and credit is due to Leone and his writing partners for transposing a story set in feudal Japan to 19th century Mexico, and swapping a swordsman for a gunslinger with relative ease. There's an irresistible symmetry at work here between Kurosawa and Leone's film. Yojimbo filters the classic iconography of the American Western (the ramshackle frontier town, the mysterious stranger) through a Japanese mythology, whereby Leone absorbs this gene-splicing and returns it back to the Western. I like to imagine Leone bent over a moviola in Rome, running Kurosawa's film backwards and forwards, studying the text in detail, and if there's some truth to that, perhaps one can say that for the Italian Western (that is to say the spaghetti western), Yojimbo is the archetype of the archetype.

Watching A Fistful of Dollars again, I was struck by the ghostly elements of the film - the desolate, lonely town, the eerie business in the graveyard; and while dried up desert towns and cemeteries full of fallen loved ones yearning for vengeance were a common setting in American Westerns, in A Fistful of Dollars, these elements assume an almost Gothic Horror atmosphere. I'm tempted to look at the Italian fantasy films of the period, when a certain Gothic flavor that was developing with films like I Vampiri, Black Sunday, and Hercules in the Haunted World, but I need only to glance back to Yojimbo and see a similar sense of phantasmagoria at work. If one was working through Kurosawa's filmography in strict chronological order, Yojimbo might feel just a little slight after Hidden Fortress and The Bad Sleep Well, and it probably is - the film is mostly confined to 2 or 3 sparse interior and exterior locations, but this limited, confined use of space lends the film a claustrophobic intensity.

To push the idea further, the town in Yojimbo feels just that little bit odd - apart from the warring gangsters, it appears that most ordinary folk have fled or remain shut up in doors, and the town feels less like an earthly plain and more like what the Japanese call Meido, a gloomy, shadowy afterlife where souls await promotion to Heaven or get flushed down to Hell. When Sanjuro wanders into the town, the rival clans are locked in an infernal stalemate where neither side has the upper hand. Even Sanjuro inadvertently finds himself stuck in this limbo perhaps for his roguish deeds, and is redeemed when he frees the captive wife of the local farmer and unites her with the family. For his uncharacteristic good work, Sanjuro escapes certain death after he is mashed to a pulp and is smuggled out of the town in a coffin to recuperate at a cemetery.

Yojimbo's eerie setting must have reverberated with Leone, because the town in A Fistful of Dollars are also strangely empty, apart from the inn-keeper, the ever busy coffin maker, and the family trapped within the Rojo-Baxter feud. Leone also re-stages the rescue of the imprisoned woman, and gives it an unmistakable religious bent. When the Stranger warns the family to get out of town, it reminds one of the angel from Matthew's New Testament warning Joseph and Mary to take Jesus to Egypt to avoid execution by Herod. The little boy whom the Stranger reunites with his mother, in case anyone missed the symbolism is named Jesús. Later when the Stranger is almost beaten to death, he duly escapes in a coffin, but in a slight departure from Yojimbo, the Stranger takes refuge in a mine (which is an underworld of sorts!). The cemetery location is in fact used earlier in the film, when the Stranger props up two dead soldiers against a tombstone, a ghoulish part of the Stranger's plan to further weaken the warring the families. If the Bodyguard and the Stranger emerge from their ordeals stronger and wilier, Leone playfully lends his man pseudo-supernatural powers in the climax of A Fistful of Dollars, when the Stranger emerges from a cloud of dust and appears impervious to Gian Maria Volonté's bullets, much to his astonishment, before the Stranger reveals a bullet-proof metal vest.

It's perhaps not a stretch to say that Yojimbo is a better film than A Fistful of Dollars. Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone, indeed Toshiro Mifune and Clint Eastwood, were at very different junctures of their careers at the time they made their respective films. Kurosawa had a string of masterpieces under his belt when he made Yojimbo, while Leone was still a few years away from making his. Yojimbo is better plotted, better shot and better acted, but the irony of course is that it's Leone's film that has made the greater mark on Cinema. Where Yojimbo is elegant, with its luminous, noirish black and white photography and beautiful, dexterous swordplay, A Fistful of Dollars fizzes with a youthful energy and an unashamed vulgarity (as does most of Leone's films it must be said), and from the gaudy, comic book style credit sequence to the brash, sudden outbursts of explicit messy violence, it feels like a stick of dynamite tossed at the traditional American Western. A Fistful of Dollars was pivotal is resuscitating the ailing Western whose conventions were beginning to fall behind the times. Indeed, with one kick of the saloon door, it changed the face of the western all'italiana forever and spawned thousands of imitators and variations for years to come.

------------

Notes

------------

1. Had I copy of the film on DVD, I might have watched Walter Hill's 1996 film (and authorized Yojimbo remake) Last Man Standing. In fact I've not actually seen Hill's film so I made no mention of it in the post.

Notes

------------

1. Had I copy of the film on DVD, I might have watched Walter Hill's 1996 film (and authorized Yojimbo remake) Last Man Standing. In fact I've not actually seen Hill's film so I made no mention of it in the post.

Wednesday 3 June 2020

Until the End of the World artwork

I wanted to include this as part of yesterday's musing on the British Thief poster, but it proved too awkward a fit, so it gets its own post today. Presenting the original artwork for the 1992 UK Entertainment In Video VHS edition of Until the End of the World, Wim Wenders' globe-trotting science fiction adventure.... I speculated yesterday that Thief's lukewarm performance in the US might have been due to the artwork designed for the US one-sheet poster, which gives the impression the film is more a science fiction thriller than a tough urban crime film, and as I was putting the post together, the artwork for EIV's VHS edition of Until the End of the World came to mind. I remember renting this tape out in 1992 and being disappointed the film didn't deliver on the promise of the beautiful nebulous airbrush painted sleeve which has a Cyberpunk/William Gibson feel to it, quite unlike the actual film. I'm thinking back now to those formative film watching years, and Until the End of the World was most likely my first Wim Wenders, and what an inauspicious introduction it was: EIV's tape contained the vastly cut down 151min version of the film, and no wonder I thought the film a confusing and alienating experience. In the subsequent years I discovered much greater riches with Wim Wenders' German films, plus his two finest films, Paris Texas and Wings of Desire, and with those under my belt, I was intrigued enough to revisit Until the End of the World in 2005, when Studio Canal put out the complete 287min cut (4 continents, 4 DVDs). Over the years my fondness for the film has grown considerably, and I now consider it one of the more interesting and rewarding films of the 90's.

Tuesday 2 June 2020

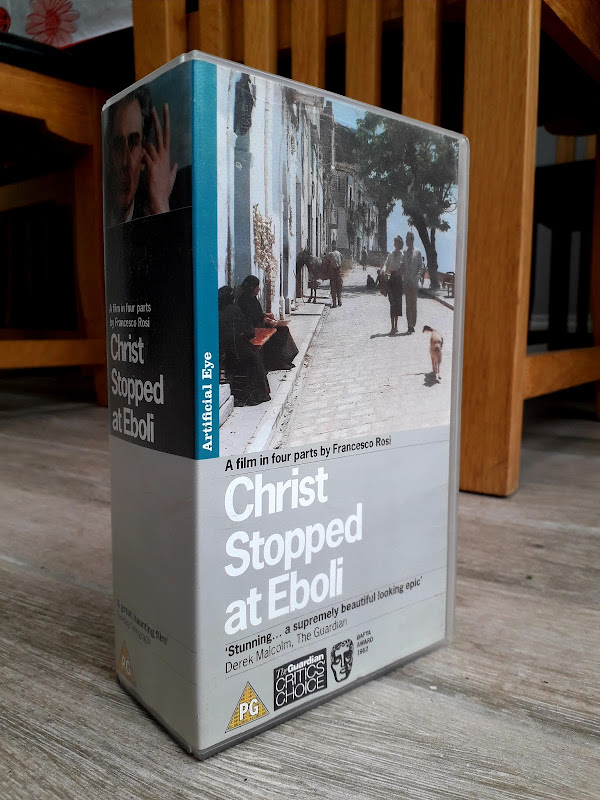

Thief Poster

British quad for Thief... I'm only posting this to stave off the temptation to buy this gorgeous poster which I spotted on ebay earlier. I'm thinking about where it could go in the house but I’ve pretty much used up all the wall space my wife will allow me. It's a beautiful piece of design, and as far as I know this artwork is exclusive to the British release, capturing well the gaudy, neon look of those painted wet streets. The film's poor performance in the US no doubt prompted United Artists to devise a different marketing strategy for the film's international release, and the decision to go with a more conventional crime film concept was understandable. As much as I love the film's US one-sheet poster - a transparent rendering of James Cann's face against a furnace of white-hot sparks, it does suggest a futuristic, hi-tech science fiction thriller rather than a tough, no-nonsense crime film. The Violent Streets re-title doesn’t have the modernist cool of the original title, but this film was made in Chicago, and reportedly filmed in some very rough neighborhoods, so the re-title feels well earned. To cover all bets, the British poster modified the original tagline: "Tonight, his take home pay is $410,000...tax free", adding “He’s a thief”, but it doesn't quite work as well as reading it on the American poster. Michael Mann's film arrived at the beginning of the 80's, and reflecting on the tagline with its focus on aggressive, deregulated money-making, it feels very zeitgeisty. Not quite the kind of laissez-faire economics Reagan promoted but nonetheless one imagines the profit potential of the thief's line of work appealed to the burgeoning yuppie class and the obsession with fast money.

My only quibble about the British poster is the awkward promo insert for Tangerine Dream's soundtrack, which I presume was due to the confusion of the album retaining the original film title and the US one-sheet artwork. In fact the first UK pressing of the soundtrack came with a hype sticker which advised: "The soundtrack of the film re-titled Violent Streets" lest there be any doubt of the connection. I'm listening to the soundtrack now as I put this post together and it's easily the group's best soundtrack work, much more so than Sorcerer I think - the opening section of the film scored to the track Diamond Diary is arguably their finest moment on film. I mentioned earlier that the US poster may have misled people into thinking the film was some kind of dystopian science fiction but the look of the film coupled with Tangerine Dream's score does lend the impression that the film is taking place not quite in the present, but perhaps a few years in the future. Certainly, the three-dimensional look of the nocturnal city, the street and signage lighting reflected in the wet alleyways and roads, creates a striking layered density that anticipates the look of Blade Runner's 21st century Los Angeles...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)